You’ve spotted a beautifully carved chair at a flea market, but is it a genuine 18th-century treasure or a modern reproduction? Understanding the distinct types of antique chairs is the key to unlocking their true value and history. That seemingly ordinary wooden seat could be a $500 Windsor or a $5,000 Chippendale original—depending on subtle details only informed collectors recognize. Without proper identification, you risk overpaying for reproductions or missing hidden gems. This guide reveals exactly how to distinguish authentic antique chair styles by examining construction techniques, materials, and period-specific features. You’ll learn to spot the hand-carved acanthus leaves of true Chippendale designs versus machine-made copies, identify the native woods in genuine Windsors, and decode maker’s marks that dramatically increase value.

Mastering antique chair identification transforms you from a casual shopper into a confident collector. Whether you’re building a period-appropriate living room or hunting investment pieces, recognizing these 10 essential types of antique chairs prevents costly mistakes and reveals stories woven into every splat and stretcher. Let’s uncover the craftsmanship secrets that separate museum-quality pieces from mass-produced fakes.

Wingback Chairs: Spot Authentic Queen Anne vs. Victorian Copies

Why Cabriole Legs Reveal True Age

Queen Anne wingback chairs (c. 1720-1750) feature gracefully curved cabriole legs ending in delicate pad feet—not the bulbous ball-and-claw feet of later Chippendale designs. Examine the wings: authentic pieces integrate them seamlessly into the back frame with organic curves, while Victorian reproductions (1850-1900) attach wings as separate elements creating a “bolted-on” appearance. The seat rail should show hand-cut dovetail joints with slight irregularities; machine-cut dovetails indicate post-1860 production.

Critical Checkpoint: Run your fingers along the wood grain where wings meet the back. Originals display continuous grain flow, whereas reproductions show abrupt interruptions at attachment points.

Upholstery Tells the Real Story

Original Queen Anne wingbacks used horsehair or straw stuffing with linen under-upholstery, visible through small tears in seat fabric. Victorian copies substituted coir (coconut fiber) and cotton, often with machine-stitched seams. Authentic pieces show uneven wear patterns from centuries of use—never uniform “distressing” applied artificially.

Pro Tip: Smell the stuffing through fabric holes. Horsehair emits a distinct hay-like odor; synthetic stuffing smells chemical.

Chippendale Chairs: Decoding Hand-Carved vs. Machine-Made Details

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/chippendale-style-furniture-148836_FINAL-20a2d4c8390c44d9b64985aad11d2275.png)

Ball-and-Claw Foot Authenticity Test

True 18th-century Chippendale ball-and-claw feet display asymmetrical carving where claws grip the ball with varying pressure—no two feet match identically. Machine-made Victorian copies (1870-1920) feature perfect symmetry and unnaturally sharp claw tips that feel “frozen.” Check the ball’s underside: originals have subtle hand-tool marks, while reproductions show smooth, machine-polished surfaces.

Red Flag: If the ball sits flush against the floor with no gap beneath, it’s a reproduction. Authentic claw feet always have a slight lift.

Splat Carving Depth Matters

Examine pierced back splats with Chinese or Gothic motifs. Genuine Chippendale work shows deep, shadow-rich carving (up to 1/2 inch deep) with smooth transitions between layers. Victorian copies have shallow, flat carving (under 1/4 inch) with visible machine-router marks. Hold the chair sideways under bright light—authentic pieces cast dramatic shadows.

Value Impact: A single hand-tool mark in the splat’s deepest recess can double a chair’s value.

Windsor Chairs: Wood Species = Dating Secret

Why Elm Seats Signal 18th-Century Origin

Authentic 1700s Windsors use elm for seats (resistant to splitting), oak for legs, and yew/ash for bent spindles. Victorian reproductions (1840-1900) substituted cheaper beech or birch. Press your thumbnail into an inconspicuous seat area: elm yields slightly with a fibrous feel; beech resists firmly. Original green paint (from iron oxide and vinegar) appears only on 18th-century country examples—never on mahogany dining Windsors.

Quick ID: Measure spindle thickness. Pre-1800 Windsors have irregular spindles (5/8″ to 3/4″); machine-made copies are uniform (exactly 5/8″).

Bergère Chairs: Caning and Cushion Clues

Hand-Woven Cane Patterns Exposed

Genuine 19th-century French bergères feature natural cane with irregular strand widths (1/8″ to 3/16″) and slight color variations from hand-dyeing. Machine cane shows identical strand thickness and uniform honey-brown coloring. Run your palm across the caning—authentic pieces feel subtly uneven; reproductions glide perfectly smooth.

Must-Check: Lift removable cushions. Original horsehair stuffing forms lumpy, resilient mounds; modern foam sits unnaturally flat.

Balloon Back Chairs: The Set Completeness Premium

Why Matching Sets Command 300% More

Victorian balloon-back dining chairs (1830-1860) rarely survived intact. A lone chair sells for £150-£400, but a matching set of eight with identical Cuban mahogany grain and French polish patina fetches £4,000+. Inspect seat rails for subtle color variations—original sets show consistent wood tone; mismatched chairs indicate later additions.

Provenance Shortcut: Check for auction house labels underneath seats. Christie’s or Sotheby’s stickers from pre-1950 sales verify authenticity.

Curule and Savonarola Chairs: X-Frame Authentication

Brass Bracket Dating Technique

Roman-inspired curule chairs (revival period 1840-1900) feature hand-forged brass brackets at X-frame intersections. Early pieces use soft, malleable brass with hammer marks; post-1920 copies use hard, machine-stamped brass. Press a fingernail into bracket edges—authentic brass dents slightly; modern alloys resist.

Savonarola Secret: True 15th-century revival chairs have Gothic tracery carved through the X-frame, not applied on top. Shine light through side panels—reproductions show solid wood blocking light.

Regency Chairs: Exotic Wood Verification

Rosewood vs. Stained Mahogany Trick

Regency chairs (1811-1830) exclusively used genuine rosewood or zebra-wood—not stained mahogany. Scratch an inconspicuous spot with a pin: rosewood reveals dark purple undertones; stained mahogany shows reddish brown. Authentic pieces display natural wood figuring without filler—run a credit card along grain; reproductions feel slightly bumpy where filler fills pores.

Sabre Leg Test: Authentic curved legs show hand-reeded fluting with irregular spacing. Machine-made versions have mathematically perfect reeding.

Morris Chairs: Recliner Mechanism Inspection

Notched Position Authenticity

Original Morris chairs (1860-1900) feature hand-cut notches in the reclining mechanism allowing 3-5 precise back angles. Reproductions have smooth, continuous adjustment. Shake the chair firmly—authentic pieces produce a faint “click” at each notch; copies slide silently.

Arts & Crafts Proof: Look for visible pegged tenons (oak pins securing joints). Machine-made copies hide joints with veneers.

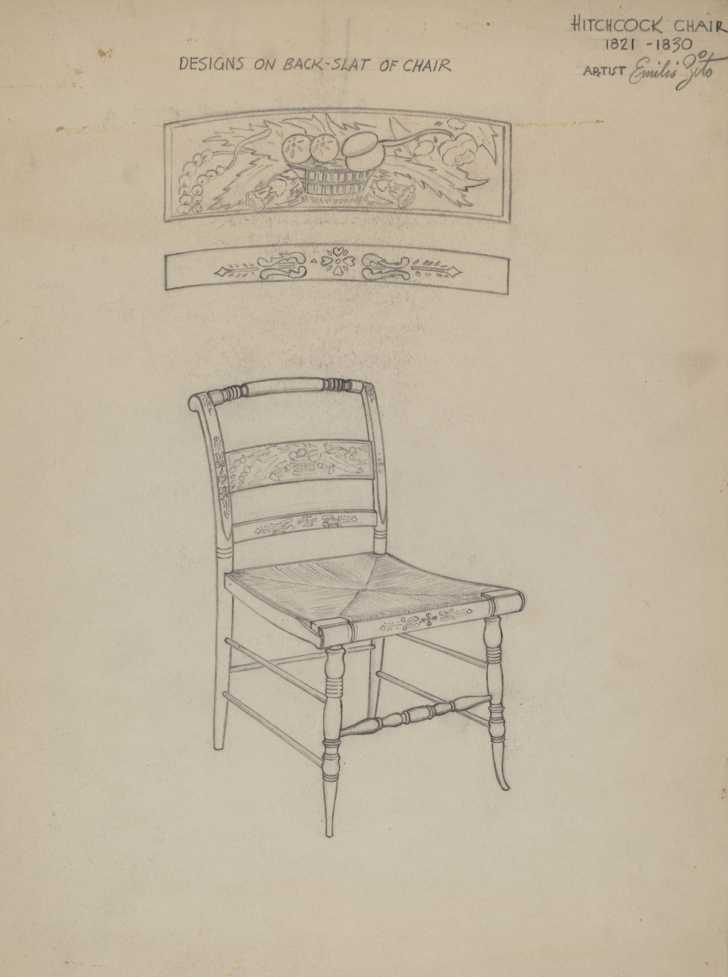

Hitchcock Chairs: Stencil vs. Hand-Painted

Gold Leaf Authenticity Check

Lambert Hitchcock’s original stenciled chairs (1818-1850) used real gold leaf over black japanned finish. Rub a cotton swab with acetone on a hidden area—gold leaf won’t transfer; paint reproductions leave yellow residue. Authentic stencils show slight bleeding at edges from hand-brushing; machine prints have razor-sharp lines.

Label Verification: Genuine “L. Hitchcock, Hitchcocks-ville, Conn.” paper labels are printed on thin, brittle paper with ink feathering into fibers. Modern copies use crisp, thick paper.

Antique Chair Identification Cheat Sheet

Wood Dating at a Glance

- Oak seats: Pre-1750 Windsors or William IV pieces

- Walnut frames: Queen Anne originals (1720-1750)

- Cuban mahogany: Victorian balloon-back dining sets

- Rosewood: Exclusive to Regency period (1811-1830)

- Elm seats: 18th-century country Windsors

Instant Reproduction Red Flags

- Phillips-head screws (invented 1930s)

- Foam rubber stuffing (post-1950)

- Machine-cut dovetails (post-1860)

- Chrome hardware (modern)

- Perfectly symmetrical carving

Construction Clues Timeline

- Hand-forged nails: Pre-1830

- Cut nails: 1830-1890

- Wire nails: Post-1890

- Glue joints: Post-1920

Maximize Your Antique Chair Value

Never Refinish Original Surfaces

An unrestored Queen Anne chair with honest wear commands 40% more than a refinished “perfect” copy. Authentic patina shows deep, warm luster from centuries of wax buildup—never uniform shine. When in doubt, preserve original finish; collectors pay premiums for untouched surfaces.

Document Every Detail Immediately

Photograph maker’s marks, labels, and wood grain patterns before cleaning. Gillows chairs (Lancaster) often have tiny “G” stamps on seat rails; Chippendale pieces may have pencil inscriptions under upholstery. Record these details in a digital log—provenance documentation can double value overnight.

Final Tip: Always inspect chairs upside down. Hidden areas reveal construction secrets: hand-tool marks on undersides, original paper labels, and wear patterns invisible from above. With this knowledge, you’ll confidently distinguish £50 reproductions from £5,000 heirlooms—turning antique chair hunting from guesswork into a profitable science. Master these types of antique chairs, and every seat tells a story you can authenticate.